Falling Asleep to Flying Toasters

Posted on Sat 20 December 2025 in Technology

Falling Asleep to Flying Toasters

You know, screen savers used to actually matter.

I don’t mean “this looks cool while I’m away from my desk.” I mean they had a job. CRTs would burn images into the phosphor if you left something up too long. So you needed motion. Constant motion.

And somewhere along the way, someone decided that if things had to move anyway, they might as well be weird.

That’s how we ended up with screen savers that weren’t just background noise, but little moments. Stuff you noticed. Stuff you remembered.

The After Dark Era

If you had a PC in the 90s, there’s a decent chance After Dark was installed on it. Even if you don’t remember the name, you remember the visuals.

Flying Toasters are the obvious one. They’re practically shorthand for “old computer.” Chrome toasters with wings just casually floating by like that was a totally normal thing to see on an office machine.

But honestly, those were just the friendly ones.

Totally Twisted Was Something Else

The ones that stuck with me came from Totally Twisted After Dark.

I saw it running on a friend’s PC and immediately realized this wasn’t passive entertainment. Some of these screen savers wanted you involved. Others just wanted to see how uncomfortable they could make you while still technically being allowed.

There was one where people bungee-jumped from the top of the screen. Most of the time it was fine. And then sometimes… it wasn’t. Cord snaps. Splat. End of story.

Another one turned the screen into a shooting gallery. Crosshairs, ammo, mimes everywhere. It was a screen saver that dared you to touch the mouse.

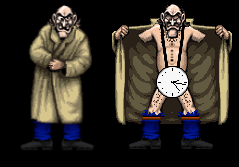

And then there was the old man.

If you know, you know.

He walks across the screen in a trench coat, muttering at you. Laughing to himself. Saying things that feel like they shouldn’t be directed at a computer user. Then he stops, turns toward you, and asks if you want to know what time it is.

You do.

He opens the coat. He’s naked. Except he isn’t, because there’s a big clock covering exactly what it needs to cover. He sways back and forth and the clock moves with him, perfectly timed.

It’s dumb. It’s juvenile. It’s absolutely ridiculous.

And it made me laugh way harder than it should have.

Still does, honestly.

Fast Forward a Few Decades

Like most things, that era got boxed up by life.

Work happened. Kids happened. Time disappeared. At some point I bought the original CD, mostly out of nostalgia, knowing full well it probably wouldn’t run anymore.

It didn’t.

And for a long time, that was fine. It sat on a shelf like a little time capsule I didn’t have time to open.

Then the house got quieter. Kids moved out. Time showed up again.

And that old thought came back: I kind of want to see how this thing actually works.

Step One: Make It Run

My first instinct was to spin up Windows 95 in a VM. Easy enough, right?

I got the startup sound, which immediately sent me back to fixing PCs for a school district. That part was great.

The rest… not so much.

Crashes. Missing DLLs. Blue screens. Rebuild after rebuild, same weird behavior. I tried different ISOs, different configs, and kept getting the same results.

Eventually it clicked that nothing was corrupted. The machine was just too fast.

Modern CPUs don’t just outperform old ones — they break assumptions. Timing loops, delays, things that were never meant to run at gigahertz speeds just fall apart.

Slowing Time Down

That’s where 86Box came in.

I set it up with what felt right without really thinking about it too hard. Pentium II. A couple hundred megahertz. Enough memory to be generous, but not ridiculous.

And suddenly Windows 95 behaved like it remembered who it was.

Totally Twisted installed cleanly. The screen savers ran. Everything worked.

Which is where curiosity officially took over.

Poking at the Files

After Dark’s setup is pretty clever. There’s an engine, and then there are these .AD files that hold each individual screen saver.

Naturally, I assumed those files were packed with sprites and sounds in some extractable format.

So I did what anyone would do first — I tried the obvious tools. Resource editors. Resource Hacker. The usual stuff that cracks open a DLL and spills out bitmaps and WAVs like candy.

Nothing.

No images. No audio. No friendly resource tables. Not even junk that looked like it wanted to be something.

At that point I backed up and asked a simpler question: what are these files, really?

Using file on Linux made things clearer. These weren’t modern PE DLLs at all — they identified as NE executables, old 16-bit Windows–era files. Windows 3.x territory. That explained why modern tools were shrugging.

What surprised me was that even tools from that era didn’t help. NE-aware resource viewers still came up empty. No bitmaps. No WAV resources. No candy spilled out at all.

That’s when it really set in: these .AD files weren’t storing assets the traditional Windows way — not then, and not now.

So I stopped treating them like executables and started treating them like raw data.

When in Doubt, Use Strings

I ran strings across the files just to see what was in there.

And buried in the noise were familiar markers. RIFF. WAVE.

That was enough.

Once I had offsets, dd did the rest. No loaders. No emulation. Just raw bytes pulled straight out of the file.

And sure enough, clean WAV audio dropped out the other side.

That alone told me these files weren’t using anything like standard Windows resource storage. Whatever Berkeley Systems did here, it was custom.

Sprites Were Another Story

The visuals didn’t give themselves up so easily.

I couldn’t find anything obvious to carve out, which suggests the drawing was happening programmatically, or at least in a format that never expected to be seen outside the engine.

So instead of extracting them, I watched them.

I ended up writing a small custom application whose only job was to take pictures. No fancy automation, no deep hooks — just a way to capture frames coming off a running system reliably.

Frame by frame. Slow. Manual in the very literal sense — stitching individual sprite cells back together by hand after capture, making sure timing and alignment still felt right.

But it worked.

Closing the Loop

Once I had audio and visuals, it felt wrong to just leave them sitting in a folder.

So I wrote a very basic screen saver in VB.NET. Nothing ambitious. Just enough to display what I’d recovered and hear those sounds again without needing the original engine.

Seeing it all move again — disconnected from where it started, but still recognizable — felt like finishing something I’d left hanging years ago.

Why I Even Bothered

This wasn’t about cracking software or proving anything.

It was curiosity. And nostalgia. And wanting to understand how people snuck humor into places where no one was really supposed to be watching.

Screen savers were never meant to be serious.

And maybe that’s why they stuck with me.